About five o'clock, as Maurice and his companions were finally falling back to seek the shelter of the barricades in the Rue du Bac, descending the Rue de Lille and pausing at every  moment to fire another shot, he suddenly beheld volumes of dense black smoke pouring from an open window in the Palace of the Legion of Honor. It was the first fire kindled in Paris, and in the furious insanity that possessed him it gave him a fierce delight. The hour had struck; let the whole city go up in flame, let its people be cleansed by the fiery purification! But a sight that he saw presently filled him with surprise: a band of five or six men came hurrying out of the building, headed by a tall varlet in whom he recognized Chouteau, his former comrade in the squad of the 106th. He had seen him once before, after the 18th of March, wearing a gold-laced kepi; he seemed by his bedizened uniform to have risen in rank, was probably on the staff of some one of the many generals who were never seen where there was fighting going on. He remembered the account somebody had given him of that fellow Chouteau, of his quartering himself in the Palace of the Legion of Honor and living there, guzzling and swilling, in company with a mistress, wallowing with his boots on in the great luxurious beds, smashing the plate-glass mirrors with shots from his revolver, merely for the amusement there was in it. It was even asserted that the woman left the building every morning in one of the state carriages, under pretense of going to the Halles for her day's marketing, carrying off with her great bundles of linen, clocks, and even articles of furniture, the fruit of their thieveries. And Maurice, as he watched him running away with his men, carrying a bucket of petroleum on his arm, experienced a sickening sensation of doubt and felt his faith beginning to waver. How could the terrible work they were engaged in be good, when men like that were the workmen? . . .

moment to fire another shot, he suddenly beheld volumes of dense black smoke pouring from an open window in the Palace of the Legion of Honor. It was the first fire kindled in Paris, and in the furious insanity that possessed him it gave him a fierce delight. The hour had struck; let the whole city go up in flame, let its people be cleansed by the fiery purification! But a sight that he saw presently filled him with surprise: a band of five or six men came hurrying out of the building, headed by a tall varlet in whom he recognized Chouteau, his former comrade in the squad of the 106th. He had seen him once before, after the 18th of March, wearing a gold-laced kepi; he seemed by his bedizened uniform to have risen in rank, was probably on the staff of some one of the many generals who were never seen where there was fighting going on. He remembered the account somebody had given him of that fellow Chouteau, of his quartering himself in the Palace of the Legion of Honor and living there, guzzling and swilling, in company with a mistress, wallowing with his boots on in the great luxurious beds, smashing the plate-glass mirrors with shots from his revolver, merely for the amusement there was in it. It was even asserted that the woman left the building every morning in one of the state carriages, under pretense of going to the Halles for her day's marketing, carrying off with her great bundles of linen, clocks, and even articles of furniture, the fruit of their thieveries. And Maurice, as he watched him running away with his men, carrying a bucket of petroleum on his arm, experienced a sickening sensation of doubt and felt his faith beginning to waver. How could the terrible work they were engaged in be good, when men like that were the workmen? . . .

Another fire had broken out in an hotel not far away. And all at once a comrade came running up to tell him that the enemy, not daring to advance along the street, were making a way for themselves through the houses and gardens, breaking down the walls with picks. The end was close at hand; they might come out in the rear of the barricade at any moment. A shot having been fired from an upper window of a house on the corner, he saw Chouteau and his gang, with their petroleum and their lighted torch, rush with frantic speed to the buildings on either side and climb the stairs, and half an hour later, in the increasing darkness, the entire square was in flames, while he, still prone on the ground behind his shelter, availed himself of the vivid light to pick off any venturesome soldier who stepped from his protecting doorway into the narrow street. . .

Those were the orders, were they not? to fire the adjacent houses before they abandoned the barricades, arrest the progress of the troops by an impassable sea of flame, burn Paris in the face of the enemy advancing to take possession of it. And presently he became aware that the houses in the Rue du Bac were not the only ones that were devoted to destruction; looking behind him he beheld the whole sky suffused with a bright, ruddy glow; he heard an ominous roar in the distance, as if all Paris were bursting into conflagration. Chouteau was no longer to be seen; he had long since fled to save his skin from the bullets.

Les Pétroleuse

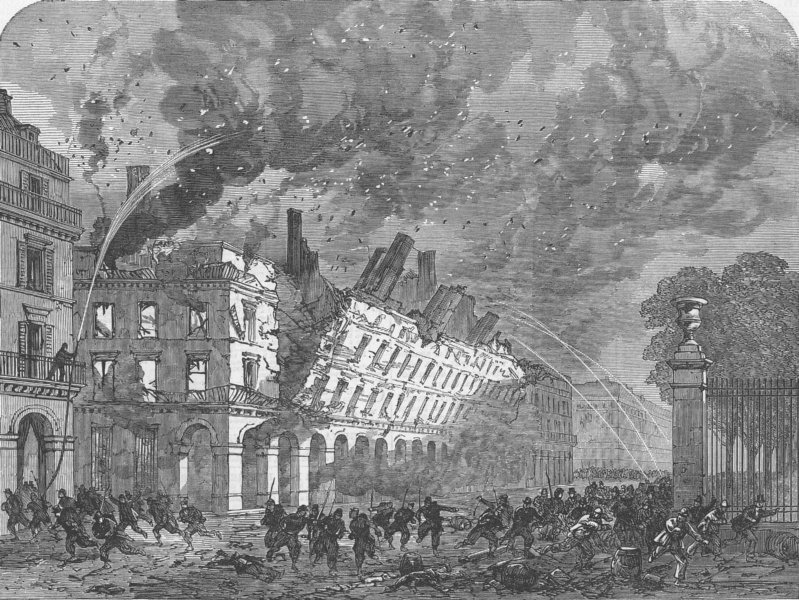

This print presents an image of the "Pétroleuse," the women accused of setting fire to buildings duing the suppression of the Paris Commune. It is quite possible that these actions were exaggerated, but an important element in the memory of the Commune after 1871 was the belief that demonic women had set out to destroy the city. Thus, images such as this were crucial to more conserative views of these events.